Canada is one of five countries which together hold more than 70 per cent of the world’s wildlife, a new study shows.

More than 77 per cent of the Earth’s land surface has been modified by humans, according to the study from the University of Queensland and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

But the last truly wild places are mostly found in Russia, Canada, Australia, Brazil and the U.S.

The report, titled “Protect the last of the wild” and published in Nature, calls on the international community to protect these important spaces.

Only about 23 per cent of Canada’s land habitats are still wild, and the oceans are even worse off – with only 13 per cent untouched by humans. That makes for about seven million square kilometres of wild land and another two million square kilometres of untouched ocean. Canada’s boreal forest is the largest untouched wild space in the world.

The study defined wild places as areas that do not have industrial level activity – but could have local communities such as Indigenous peoples who hunt and fish on the land. Antarctica wasn’t included in the study because the report says “the indirect effects of human activities there are harder to measure.”

Keeping these wild spaces intact will mitigate the effect of climate change, the report says.

WATCH: Online maps show impact of climate change on Canada’s boreal forests

But within the last 10 years, over three million square kilometres of wild spaces have disappeared globally, report co-author Oscar Venter explained.

Venter, who is an associate professor at the University of Northern British Columbia, said Canada and the other four countries are in a unique position to shape environmental policy.

“So what happens in Canada, what happens in Brazil … over the next decades have a really big impact on the last wild places,” Venter said.

While Canada has some of the largest wild spaces, there has been increasing pressure to open it up to industry with projects like Ontario’s ring of fire mining proposal.

But environmental law professor Dayna Scott of Osgoode Hall Law School of York University says Canada needs a broader plan.

“It’s often talked about as one-off decisions, ‘Do we want this mine or not?’ and not necessarily standing back to create a broader-based vision,” Scott told Global News.

“Instead we get what people call a cumulative impact, something like death by a thousand cuts.”

WATCH: UN climate change report: What half a degree of global warming means

The report calls on local governments and global organizations to act to preserve the wild spaces we have left, by doing things like consulting Indigenous people and incentivizing private conservation.

“Keeping Earth’s remaining marine wilderness off-limits to exploitation should be a key component of the new treaty,” the report reads.

New government in Brazil adds worries about Amazon rainforest

The Amazon rainforest in Brazil is another major wild space that is named in the report – but Venter echoed global concerns that its newly elected government could threaten the environment.

“Brazil is incredibly important globally,” Venter said.

Environmentalists around the world have raised concerns with president-elect Jair Bolsonaro who has suggested merging Brazil’s environment and agriculture ministries and threatened to pull out of the Paris climate accord.

“His reckless plans to industrialize the Amazon in concert with Brazilian and international agribusiness and mining sectors will bring untold destruction to the planet’s largest rainforest,” Christian Poirier, the program director of Amazon Watch, said in a statement shortly after the election.

Venter explained that while Brazil had previously been moving in the right direction, the environmental community will be watching to see whether all their “hard work will be undone.”

“A really hard truth is that a government can come in and within one mandate make decisions that fragment these ecosystems and have negative effects that are contrary to the interest of most people in the world,” Scott explained.

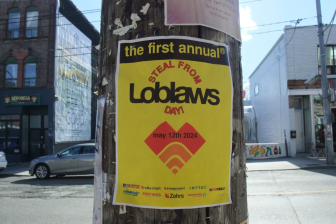

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

Comments