An Osgoode Hall Law School graduate who was involved in Chile’s historic effort to create a new, progressive constitution said she’s still saddened that voters overwhelmingly rejected the proposal in a referendum in September.

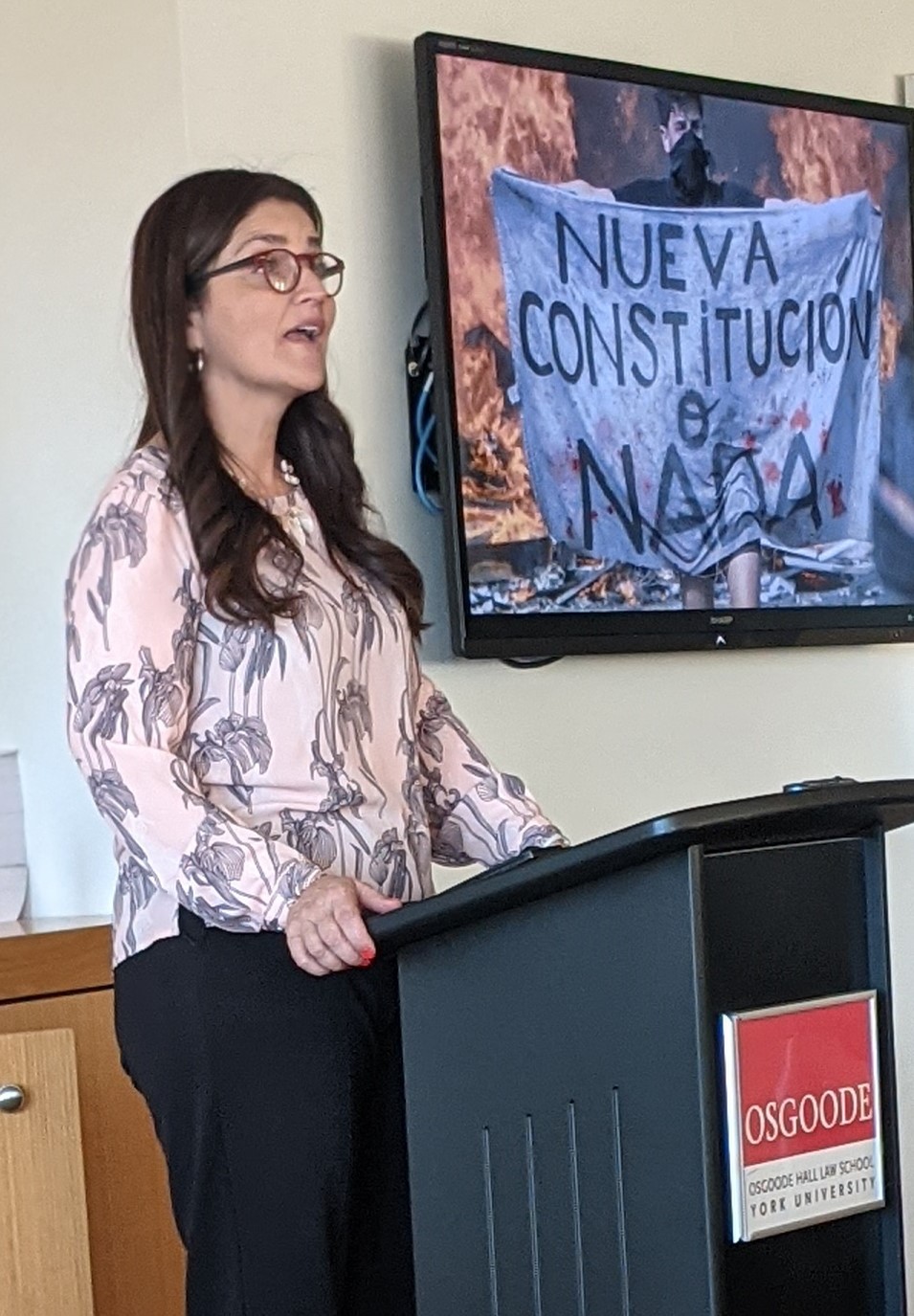

“I was optimistic until the very end,” Amaya Alvez, a 2011 Osgoode PhD graduate and a professor of law at University of Concepción in Concepción, Chile told a group of Osgoode students during a Oct. 24 talk at the law school.

“But then we voted on Sept. 4 and we lost 60-40,” she added. “It was a huge gap and I don’t know exactly why.”

Alvez was one of 155 members of the Chilean Constitutional Convention elected in May 2021 to draft the proposed law, which was intended to replace the constitution established by the military dictatorship of former president Augusto Pinochet in 1980. The Constitutional Convention met from July 2021 to July 2022.

The initiative was prompted by violent protests against inequality in 2019 and a national plebiscite in October of that year in which 78 per cent of voters called for a new constitution.

But when Chileans were asked to pass judgment on the final draft in September under a new system of mandatory voting, 62 per cent said no and only 38 per cent endorsed it.

Alvez said the convention’s goal was to produce a “transformative constitution” that, if passed, would have been one of the most progressive in the world, with key provisions supporting direct democracy, gender parity, Indigenous rights and protections for the environment.

As a legal scholar, she said, the result will provide her with years of research material. But it leaves many – including herself – feeling bitterly disappointed and despondent.

“I’m sad, but also concerned,” she told her Osgoode audience. “It was an interesting academic exercise, but we haven’t solved anything.”

Alvez attributed the yes side’s defeat in part to a well-funded disinformation campaign paid for largely by “powerful economic agents.” According to some reports, the campaign involved some 8,000 unique Twitter accounts that spread a steady stream of criticism for the convention members and their proposed constitution. Critics called the convention’s proposal “radical” and “fiscally irresponsible.”

“Because I’ve never been a politician, I have to say I was naïve about how lobbying happens,” said Alvez. “We needed a communications strategy from the beginning.”

But in retrospect, she added, the approval process in some ways was flawed. “It was wrong to put an everything or nothing question up for debate,” she argued.

At the same time, the many changes proposed in the draft constitution may have made people fearful, she speculated. “Sometimes I think law is a cultural product,” she observed, “and maybe we were not prepared for it.”

Alvez, who traces her maternal ancestry to South America’s Mapuche Indigenous group, said she was shocked that even the majority of Chile’s Mapuche citizens voted against the proposed constitution, despite its Indigenous protections.

In the aftermath of the defeat, Chilean President Gabriel Boric has publicly stated that he will work with the National Congress of Chile and civil society to develop a new process for constitutional reform. But Alvez said the new process will depend more heavily on established experts and, in some ways, will not be as democratic.

In retrospect, Alvez said the experience was one of the most challenging times in her life – even harder than doing her PhD. But she still urged the law students to seize opportunities for public service.

“We need to do public service – all of us, in different ways at different times,” she said.