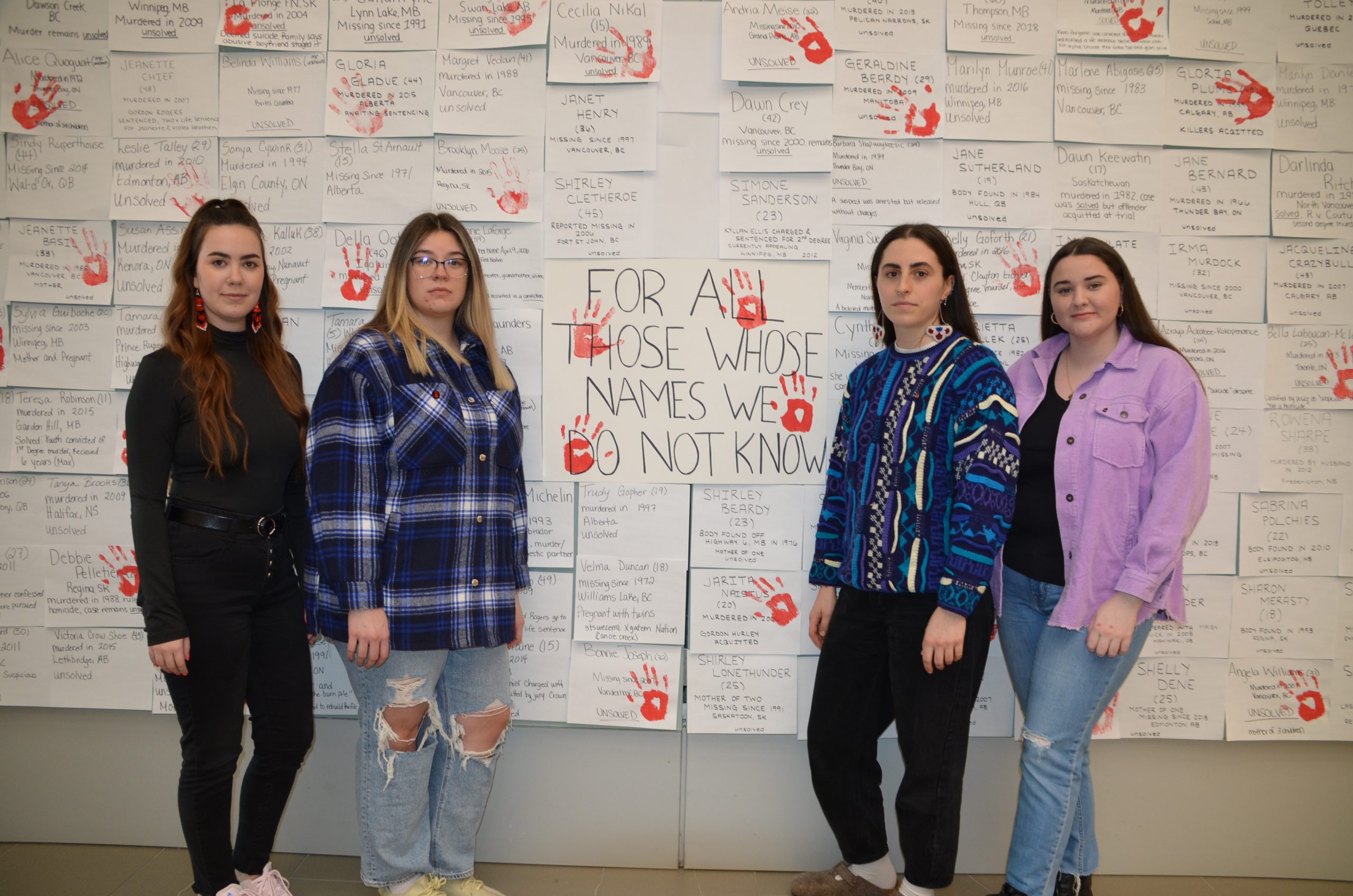

As JD students Megan Delaronde ’23 and Annika Butler ’23 wrote out the names and stories of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls recently, one thing became painfully clear: the Canadian justice system has never solved the vast majority of cases.

Butler, the co-chair of the Osgoode Indigenous Students’ Association (OISA), Delaronde, OISA’s director of cultural and community relations, and 1L Representatives Sage Hartman and Hannah Johnson wrote out 300 of the stories for OISA’s RedDress Week Feb. 13-17, posting them throughout the main floor of the law school along with a number of red dresses”. They selected the stories from thousands of cases chronicled in a database maintained by the Gatineau, Que.-based Native Women’s Association of Canada.

“There are stories that I have written out that will stick with me,” said Delaronde, a member of the Red Sky Métis Independent Nation in Thunder Bay, Ont.

She and Butler, a member of the Mattawa/North Bay Algonquin First Nation, pointed to examples like a nine-month-old baby girl who died in foster care – no charges were ever laid – or 20-year-old Cheyenne Fox of Toronto, whose three 911 calls just prior to her 2013 murder went unanswered.

“I think a lot of the time this problem stays abstract for people who aren’t Indigenous,” said Delaronde. “One of the things we were hoping to accomplish with our names wall was to show the vastness of this problem and for people to understand that these aren’t just names. Many of them were mothers and the vast majority of these cases have gone unsolved.”

Many of the postings on the wall did not carry a name. “A lot of the names of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) we don’t know,” said Butler, “but we still wanted to hold a place in our hearts for them.”

She noted that official statistics kept by police typically underestimate the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada compared with records kept by the Native Women’s Association and other Indigenous organizations and communities.

OISA’s RedDress Week this year was the most extensive in the club’s history. Inspired by Métis artist Jaime Black’s 2010 art installation, the REDress Project, RedDress events are typically held in May to raise awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women. But because the academic year is usually over by May, Delaronde said OISA decided to schedule the event in February.

She said the timing seemed appropriate considering one of the latest reminders of the continuing tragedy: the recent murders of four Indigenous women in Winnipeg: Rebecca Contois, 24, Marcedes Myran, 26, Morgan Harris, 39, a mother of five children, and a fourth unidentified woman who has been named Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe – Buffalo Woman.

“We wanted to ramp it up this year so we poured our hearts into it,” said Delaronde.

The group also organized a trivia night event that raised almost $1,000 for the Native Women’s Association of Canada.

Butler and Delaronde said that first-year reps Hartmann (Red River Métis) and Johnson (Secwepemc Nation) also played a key role in organizing the event, with support from OISA members Levi Marshall and Conner Koe, Osgoode’s student government and Osgoode’s Office of the Executive Officer.

They also commended Osgoode and York for the support they have provided to Indigenous students, especially York’s Centre for Indigenous Student Services and the “time and intention” Osgoode has put into hiring “top-tier” Indigenous professors.

In September, OISA organized a special event for Orange Shirt Day (also known as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation), with guest speakers and Osgoode alumni Deliah Opekokew ‘77, the first First Nations lawyer to ever be admitted to the bar association in Ontario and in Saskatchewan, and Kimberly Murray ‘93, who serves as the federal government’s special interlocutor on unmarked graves at former residential schools. In March, it plans to organize a Moose Hide Campaign Day. The Moose Hide Campaign is nationwide movement of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians from local communities, First Nations, governments, schools, colleges/universities, police forces and many other organizations committed to taking action to end violence against women and children.